Uncovering hidden prejudices when ordering blockchain transactions

Table

Summary/Zusammenfassung

Publications

Recognition

1. Chapter: Introduction

-

Introduction

1.1 Overview of nature guarantee

1.2 Review of the thesis

Chapter 2: Background

2.1 Block Chains and Smart Contracts

2.2 The rules for setting the importance of transactions

2.3 Setting of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

2.4 Decentralized Management

2.5 Chip Chain Scales with layer 2.0 solutions

Chapter 3. The order of the order of the importance of transactions

-

The order of the order of the importance of transactions

3.1 methodology

3.2 Analyzing the following norm

3.3 Investigating the offenses of the norm

3.4 Dark Defense Transactions

3.5 Summary notes

Chapter 4. Setting of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

-

Setting of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

4.1 methodology

4.2 on the transparency of the application

4.3 of the transparency of a priority

4.4 Summaries

Chapter 5. Decentralized management

-

Decentralized management

5.1 Methodology

5.2 Leadership attacks

5.3 Compound Management

5.4 Summary notes

Chapter 6. Related to work

6.1 The rules for setting the importance of transactions

6.2 Setting of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

6.3 Decentralized Management

Chapter 7. Discussion, restrictions and future work

7.1 Ordering a transaction

7.2 Transparency of the transaction

7.3 Vote Distribution to change smart contracts

Conclusion

Extras

Appendix A: Further analysis of transaction priorities standards

Annex B: Additional analysis of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

Annex C: Further analysis of voting force distribution

Bibliography

In this chapter, we will study the literature related to this thesis. Let's explore the three main topics: (i) Satching of transaction priorities; (ii) the setting of priorities of transactions and transparency of the dispute; and (iii) decentralized leadership. The latter includes works that investigate the division of decision -making of the chain chain management.

6.1 The rules for setting the importance of transactions

Some recent articles suggested solutions to enforce this transaction follows a certain norm based mainly on statistical tests of potential abnormalities (Asayag et al., 2018; Lev-Ari et al., 2020; Ord and Rotentreich, 2019). However, these works were mostly theoretical because they did not contain the empirical evidence of the miners' deviation, but rather assumed that the miners could deviate. Earlier efforts also proposed the consensus algorithms to ensure a fair transaction selection (Baird, 2016; Kelkar et al., 2020; Kursawe, 2020). Kelkar et al. (Kelkar et al., 2020) proposed a consensus feature, called the Transaction Organization-Fairness and the new consensus protocols called Aequita, to create a fair capacity, in addition to the provision of continuity and residents. Many of the previous work focused on the miners to choose transactions. For example, Smartpool (Luu et al., 2017) gave the deal back from mining pools to the miners. Similarly, the well -used mining protocol stratum enhancement allows the miners to choose the desired transaction (Braiins, 2021b) through the mining pool negotiations. Again, all these previous work are mostly theoretically. On the other hand, this thesis provides empirical evidence of the miners' deviation in the current Bitcoin system.

In addition, from the point of view of the miners, justice issues have been studied in the chip chain. Passport et al. (Pass and Shi, 2017) proposed a fair chip chain, where transaction fees and block bonuses are fairly distributed between the miners, reducing the variation of mining settlements. Other studies focused on security issues, which show that miners should not extract more blocks than their fair part (Eyal and Sirer, 2018) and that the extraction prize is discharged in centralized mining pools and is therefore unfairly distributed between these miners (Romiti et al., 2019). Chen and others. To. However, this does not apply if miners are not neutral, as with Bitcoin. Contrary to these earlier work, this thesis concerns justice issues concerned from the point of view of transactions, not miners.

There is huge literature on mining stimuli. Most of it, However, Considers Only Block Rewards (Chen et al., 2019; Eyal and Sirer, 2018; Fiat et al., 2019; Goren and Spiegelman, 2019; Kiayias et al., 2016; Noda et al., 2020; Passport et al., 2017; Zhang and Preneel, 2019). As the block bonus is reduced every four years in the Bitcoin block chain, some recent analysis of work focused on how incentives change when transaction fees dominate the rewards. Carlsen et al. (Carlsten et al., 2016) showed that having only transaction fees as stimuli creates instability. Tsabary and Eyal (Tsabary and Eyal, 2018) expanded this result to more general cases, including both block bonuses and transaction fees. Easley and others. (Easley et al., 2019) proposed the overall economic analysis of the system and its well -being with different types of benefits. However, these previous works require miners following a certain standard when selecting and ordering transactions (mostly fees) and look at the miners' incentives on how much to calculate the power to disclose and when (or any equivalent). There are also previous studies that deal with prime ministers as stimulus of transaction fees (Carlsten et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018); and extensive literature on the safety of the chip circuits in general (eg (eg Gencer et al., 2018; Karame, 2016; Vasek et al., 2014)). However, these studies again focus on miners' stimuli on the mine, not on the order of transactions; For the latter, they assume that the miners follow the norm. These previous studies are therefore somewhat orthogonal for this thesis.

Only a few recent works concerned the question of how miners choose and ordered transactions, and how it was interwoven with setup. Lavi et al. (Lavi et al., 2019) and Basu and others. (Basu et al., 2019) highlighted the inefficiency of the mechanisms of the existing transaction fees and the proposed alternatives. They showed that miners may not be reliable, but without empirical evidence. Siddiqui et al. (Siddiqui et al., 2020), through simulations, showed that, with transaction fees only as incentives, miners should choose greedy transactions, increasing the latency of most transactions. They proposed an alternative selection mechanism and carried out numerical simulations. This thesis takes an additional approach: we analyze empirical evidence of miners' deviations from the standard of ordering the transaction in the current ecosystem. We are also empirically analyzed at the level of collusion in the involvement of transactions.

To our knowledge, our study is the first of its kind – creating empirical evidence of normal violations on Bitcoin – and our results help to motivate the above theoretical research.

6.2 Setting of transaction priorities and transparency of dispute

As mentioned earlier, recent work was analyzed by the impact of separate reliance on transaction fees (Carlsten et al., 2016) and with blocks of blocks (Tsabary and Eyal, 2018), as well as the ratio of waiting for stimuli and transactions (Easley et al., 2019). These earlier works assume that transactions will be forwarded to all miners and the fees offered are even between the miners. None of them recognizes the issue of transparency. Previous work also analyzed the Ethereum fee (ie gas price) to determine the gas price of the transaction provided by the mechanism (Antonio Pierro et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Mars et al., 2021; Turksonmez et al., 2021). However, the estimates of the fees in these studies and the reward -based priority schemes are not taken into account by dark or private mining.

Many of the transaction accelerator or front as a service (phrase) are platforms for both Bitcoin (btc.com, 2022; VIABTC, 2022) and ethereum (Eskandari et al., 2020; Flashbots, 2022b; Sparkpool, 2021). Transaction issuers may use such acceleration or extracurricular payment channels to hide their actual fee from competitors and avoid the foreground (Daian et al., 2020; Strehle and Ante, 2020). Tim Roughgarden (Roughgarden, 2021) discussed incentives for non-circular contracts (such as dark phases) between miners and users for first-priced auctions, and various deviations in the EIP-1559 Protocol (Butterin et al., 2019a). Roughgarden showed that the miners and users cannot strictly increase their common utility according to the EIP-1559, as chain offers can easily be replaced by off-circuit offers. However, this utility is based only on the return of the BLOCK Space offer. The author did not take into account that the utility may depend on other factors, such as transaction publishers who want to keep their actual offers for the block space hidden through out -of -chain payments, which strictly increases the chances of setting their priorities as other providers cannot offer because they are unaware of the offer.

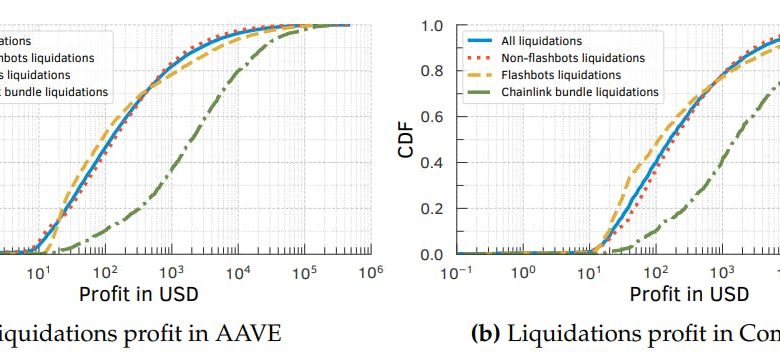

There are two jobs that analyze private mining. Streh and Ante (Strehle and Ante, 2020) studied exclusive mining (or private mining), where transaction publishers and miners met to cover transactions sent through a private network. In this case, the transactions will not be publicly disclosed until they are involved in the block; In addition, fees may remain forever opaque for everyone, as such non -circuit contracts may use Fiat currencies. Weintraub et al. To. This thesis, on the other hand, is widely studied in the context of private transactions and dark Fees Bitcoin and ethereum chip circuits. Through active measurements, we empirically show that bitcoin miners collapse and bring together collective mining pools. We show that flashbott bouquets are quite common in Ethereum and are mainly used to call for decentralized exchange agreements (DEX) to take advantage of the maximum allocated value (MEV) options. Finally, we are discussing why our findings are still in force after “merger” – Ethereum's hard fork (Ethereum Fund, 2022A, B), introduced on September 15, 2022.

Author:

(1) Johnnatan Messiah Peixoto Afonso